Interview with Ramesch Daha 20.09.2022

In August 2002 we hosted one of the most important modern artist - Ramesch Daha at Villa Decius.

She was the resident within the Artistic Scholarship of Villa Decius Institute for Culture organized in partnership with the Consulate General of the Republic of Austria in Krakow, under the “On the Road Again” project.

At the end of the residency we ask Ramesch Daha for a short summary of her stay in Krakow.

Villa Decius Institute for Culture: In your art you often combine a historical perspective with political and social narratives. What does cultural heritage mean for you? How do you treat them and perceive them—both as an artist and director of the Vienna Secession?

Ramesch Daha: My job almost always starts with some family history. I collect memories and then do research in archives, looking for materials there. My main focus is the search and study of political links between the past and the present in order to better understand and grasp the here and now. But the language of art helps me understand history in general.

VDIC: What did you work on during your several-week stay at Villa Decius?

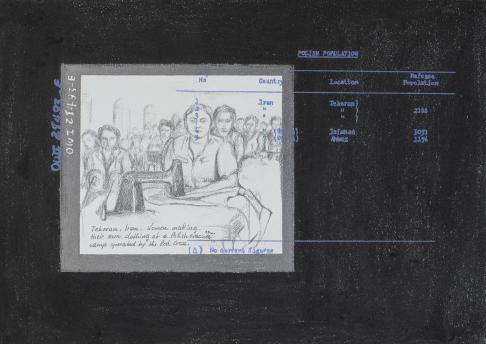

RD: During a several-week scholarship stay at Villa Decius, I continued work on my project “Unlimited history” In September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. One of the consequences of the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union was the occupation of eastern Poland by the USSR. About 1.25 million Poles were deported to various parts of the Soviet Union, of which about half a million were considered “social enemies” and deported to labor camps in Kazakhstan and Siberia. Thousands of people died from exhaustion, starvation and disease.

When the Germans broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact two years later and entered the Soviet Union, the Russians were forced to join the Allies. At that time, an agreement was signed on the reconstruction of the Polish state and the creation of the Polish army on the territory of the USSR.

Polish prisoners were informed that they would be released if they joined the newly emerging Polish army, which was to form in Iran—then occupied by Soviet and British troops. From all over the USSR, thousands of starving men, women and children, hoping to find shelter, set out on a long journey to Iran. Over 116 thousand Poles crossed the Caspian Sea by boat in order to get there. Most of them landed in the port city of Pahlavi, where they received food and were quarantined due to the rapidly spreading epidemics of malaria and typhus. Many people died of starvation or these diseases soon after arriving in Iran and were buried there.

Those who survived were taken to Tehran, where they were warmly welcomed by the Iranian government. Numerous buildings have been converted into flats, schools and cultural institutions for Polish emigrants. People who lived in harsh conditions in the camps for a long time now received clean beds and good food.

At that time, Iran was also affected by numerous sanctions imposed by the USSR. After the invasion, the Russians banned the shipment of rice to central and southern Iran, which led to food shortages, hunger and rising inflation. In preparation for the war, the Allies took over influence over the Trans-Iranian Railroad, as well as over the metallurgical industry and other resources.

Despite many of these difficulties, the Iranians openly welcomed the Poles, and the Iranian government made it easier for them to enter the country and provided them with food. Polish schools, community centers, shops, bakeries and even newspapers were established so that Poles could feel at home. There were so many refugees that numerous government buildings had to be converted into accommodation. The thousands of children who then reached Iran came from Soviet orphanages, where they ended up either because their parents died or as a result of being separated during deportation. Most of the children ended up in the Isfahan Orphanage, where the climate was mild and there was no shortage of food, which helped many children to get rid of diseases caused by poor living conditions in Soviet orphanages.

In the years 1942-45 about 2,000 children passed through Isfahan, which is why it was called “the city of Polish children”. The rest were housed in an orphanage in the eastern part of the country, in Mashhad. Schools were prepared to teach mathematics, natural sciences and other subjects in Polish. In some schools, children were taught Persian, as well as Polish and Iranian history and geography.

Most of the refugees volunteered to fight in the ranks of the newly formed Polish army, but many Poles remained in Iran until the end of the war. Most of them were children from orphanages whose parents were either dead or afraid to come by train to Iran. Many refugees also moved to other countries. Some of them decided to settle permanently in Iran and start a family there.

Many traces of the Polish presence in Iran have faded, but some are still visible today. Almost 3,000 refugees died and were buried there a few months after their arrival in Iran. These Polish graves have been preserved and are still cared for. The Polish cemetery in Tehran with 1,937 graves is the largest and most important cemetery for refugees in all of Iran.

During my stay at Villa Decius, I worked on documentation and archival video materials about these times and events.

VDIC: Did you, as an artist, find something special about Krakow that elicited your interest, or maybe surprise?

RD: Krakow is a fascinating city. I was quite impressed by the monuments of John Paul II because he was one of the most politically committed, but probably also one of the most controversial popes during the Cold War. I think this should be borne in mind, but also discussed in the context of the political stance of the Vatican at the time and now.

VDIC: Was it an additional inspiration for your work on that project right here, at Villa Decius?

RD: While working on my artistic project, the very surroundings in which I stayed — namely the Villa Decius building and its outbuildings, the places marked with many years of history — were very inspiring. But the people who work here were also extremely important — they were an invaluable help for me.

Ramesch Daha

Ramesch Daha - born in 1971 in Tehran, since 1978 she has lived in Vienna, her mother's native city, to which she moved with her family to escape from the Islamic Revolution and its resurgent fundamentalism. In her artistic work, Ramesch Daha often chooses the story of her Austro-Iranian family as well as her own biography as the starting point for her considerations of the subjective and social determinants of historical narratives. Working with a variety of media (including painting, collage, film and drawing, as well as documents from public and personal archives), she creates multi-part work complexes that combine biographical and socio-political aspects of history and arrange them into new constellations. The method of her work, based on comprehensive historical research, involves numerous travels and study visits, among others, to Vancouver, New York, London and Berlin.

Ramesch Daha has met broad international recognition with her yet uncompleted series “Victims 9/11”, in which she attempts to save the victims of the terrorist attack from oblivion by portraying every single one of them. Daha has been represented internationally in numerous solo and group exhibitions, incl. in New York, Vienna, Berlin, Stockholm, Helsinki and Augsburg.

She is the current president of the Vienna Secession.

More information at: https://ramesch-daha.com/

Ramesch Daha has met broad international recognition with her yet uncompleted series “Victims 9/11”, in which she attempts to save the victims of the terrorist attack from oblivion by portraying every single one of them. Daha has been represented internationally in numerous solo and group exhibitions, incl. in New York, Vienna, Berlin, Stockholm, Helsinki and Augsburg.

She is the current president of the Vienna Secession.

More information at: https://ramesch-daha.com/